As a lifelong wargamer and hobbyist, I’ve always yearned for ample space to spread out, and it hasn’t been until the purchase of my current house that I’ve actually had it. Wargamers know that one of the critical requirements of any session is space; it’s always a pain to begin a game knowing that there’s a ticking clock involved, that in two or three hours you’re going to have to pick up the pieces and put it all away. Longer, campaign-length scenarios become a practical impossibility, and even shorter battles often have to be truncated due to unforeseen, extra-game events. Such as dinner. Or children.

But now that I have a basement, a chair, and a large (if improvised) table, I’ve now begun to dive into some of the larger, strategic-level games I’ve owned for years but never had the opportunity to try out.

The game I’ve been going through for the last few weeks has been Pacific War, a division-level reenactment of World War II’s Pacific theater of operations from Pearl Harbor in 1941 to 1945. The game is immense, with over 1,200 counters depicting the ground, air, and naval forces of Japan, the United States, China, the United Kingdom and its Commonwealth Nations, and the Netherlands. There are two giant maps that cover India, Japan, and the Aleutians to Northern Australia, the Hawaii Islands, and the innumerable islands between.

Being a naval-dominated theater of operations, special attention has been given to the naval counters, and like many naval warfare games, the capital ships have their own counters, while the rest represent groups of similarly-classed vessels. Not so here, and for an amateur historian, it’s rather cool to learn history as you go.

I’ve never been a fan of task force-oriented counters, but the system in Pacific War works well, even for solitaire play. [For those of you unfamiliar with the concept, it’s the practice of one counter, marked with a star for the US/Allies and a rising sun for the Japanese, representing however many ships are moving together. It keeps the board from getting cluttered, adds to the potential ‘fog of war,’ and is consistent with the actual practice of task forces.]

Another concept the game gets right is searching for the enemy—you can only attack what you can spot, and a lot of battles turn on who saw whom first, or at all. The Pacific Ocean is a huge place, and with cloud cover and weather often playing a factor, some odd occurrences often crop up, as they did historically. And if you are playing against another player, make sure you take notes once your searches give you real intelligence, because you are not allowed to inspect the composition of enemy task forces otherwise. Conversely, recombine and mix up your task forces often, for obvious counterintel reasons.

Upon first opening the box, you may feel a little overwhelmed at the sheer scale of the game. Victory Games, however, has done the novice a great service by issuing a scenario booklet with a series of what they call ‘engagement scenarios’ that are solitaire, 10-15 minute games that focus on one small aspect of the game. For example, the Pearl Harbor scenario introduces the player to naval air combat, the First Invasion of Wake Island focuses on amphibious assault, and ground combat is covered in the invasion of India. Each scenario is lopsided and wouldn’t be suitable for two players, but is highly instructive in a compartmentalized way.

I've just finished my first battle scenario, "The Relief of Wake Island." This was an aborted relief effort that took place in December 1941 shortly after the bombing at Pearl. Wake had already fended off one feeble invasion attempt by the Japanese (the only amphibious invasion of the Pacific war to fail), and now they were back with significantly increased numbers. The US had three carriers in the area, but the Saratoga lolly-gagged its way to the battle, basically ruining any chance for a reasonable defense. Although the Marines fought valiantly, it can be argued that the Navy was right to abandon Wake, because a victory at Wake would probably have drawn in major Japanese attention (4 additional carriers were in cruising range)while not achieving much strategically. Even if they had retained ?Wake, it would have been difficult to hold. Nevertheless, it was the low point of the US in the war, with the Marines, seeing no relief was forthcoming, surrendering the remainder of their forces on Christmas Day.

But what if Vice-Admiral Pye had decided the risk the entire Pacific Fleet anyway? This is where I enter.

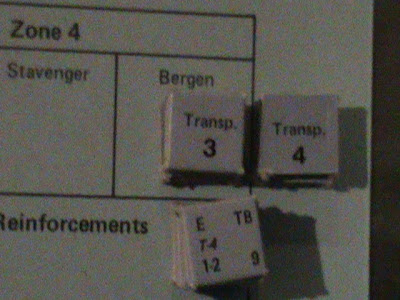

Cycle 1: The Allied and Japanese forces move into position with either failed or unsuccessful searches.

Cycle 2: 2-engined bombers from Kwajalein attack the CV New Orleans, but are repulsed by AA. Meanwhile, airstrikes from the CV's Soryu and Hiryu catch the remaining Marine Wildcats on the ground. Elsewhere, a Benson-class destroyer is instrumental in the sinking of Fubuki-class destroyers (right). On the Japanese side, the Furutaka and Aoba-class cruisers cripple the CV Saratoga, which is forced to slowly withdraw towards Pearl, while the remaining pilots transfer to the CV Lexington. Yuburi-class cruisers bombard the fortifications on Wake, whose naval guns score a hit on the Mutsuki APD's carrying the 144th Infantry Rgt.

Cycle 3: The remaining fortifications on Wake are taken out by Japanese aircraft, and the 1st Marine Battalion is bombarded and broken. US aircraft inflict heavy damage on the Soryu, but waste a golden opportunity to nail the Hiryu, missing it completely. The 144th has no problem occupying Wake (the actual battle for Wake was much costlier for the Japanese).

Cycle 4: The Japanese sink the Lexington. Its fighters simultaneously cripple the Soryu (a bit of revenge, as it and the Hiryu were 2 of the carriers that carried out the Pearl Harbor attacks two weeks earlier). But don't cry for the Lexington, because it would be sunk later on in the Battle of the Coral Sea, anyway.

Cycle 5: During the night, American fighters inflict heavy damage on the Hiryu, and as the Japanese have accomplished the requirements for victory [occupation of Wake and the destruction of more capital ships--the Lexington--than have been lost], there is no reason to hang around. It's also approaching the point in the game where if ships are going to make it back to friendly ports, they need to start heading out. Any capital ships still at sea by the end of the game will be counted as destroyed for victory purposes. The US, still hopeful of forcing a draw (they need only occupy Wake or destroy more capital ships than they lose), commit to pursuit with their destroyers and cruisers while sending the carriers back.

Cycle 6: The US, for a second turn wins the advantage, but it turns out to be to disadvantageous. They go all in with their remaining ships, but the Japanese refuse battle and withdraw. This, coupled with the movement in their own turn, give them the breathing space they need to reach their port at Ominato.

Cycles 7-14: As the US has no troops or transports to mount an invasion of their own, it's impossible in this game to wipe out defenders with only air power, and they cannot catch up to the Japanese fleet, the game is effectively over with a victory that was too close for the Japanese commander, but a victory regardless. Some better dice rolls by the US, and history could have been rewritten.

You'd think that the losses in this battle would outpace those of the historical non-battle, and you'd be correct. Losses among ground troops were similar, but losses in aircraft were twelve times those in the actual battle. At sea, during the historical battle, the Japanese lost 2 destroyers, 2 patrol boats, and had 1 light cruiser heavily damaged. There were, of course, no US naval losses.

In my reenactment, the US inflicted heavy damage on two Japanese carriers, and sank 6 destroyers and 2 patrol boats. The Japanese heavily damaged 1 carrier, sank another, and sank a Northampton-class cruiser.

I'll be taking a brief hiatus from Pacific War to try out Falkland Showdown, the 1982 conflict between the British and the Argentinians.